What does a man who lives by phrases like “Modern watches just don’t do it for me anymore”, “They don’t make them like this anymore”, and “I’m genuinely obsessed with this reference” do during his daily 2–3-hour horological rabbit hole?

He rolls up his sleeves to write a 14-page deep dive into vintage Patek Philippe chronographs.

Therapy would have been a better choice, but these tiny time-measuring pieces with their irresistible silhouettes are just – well, irresistible.

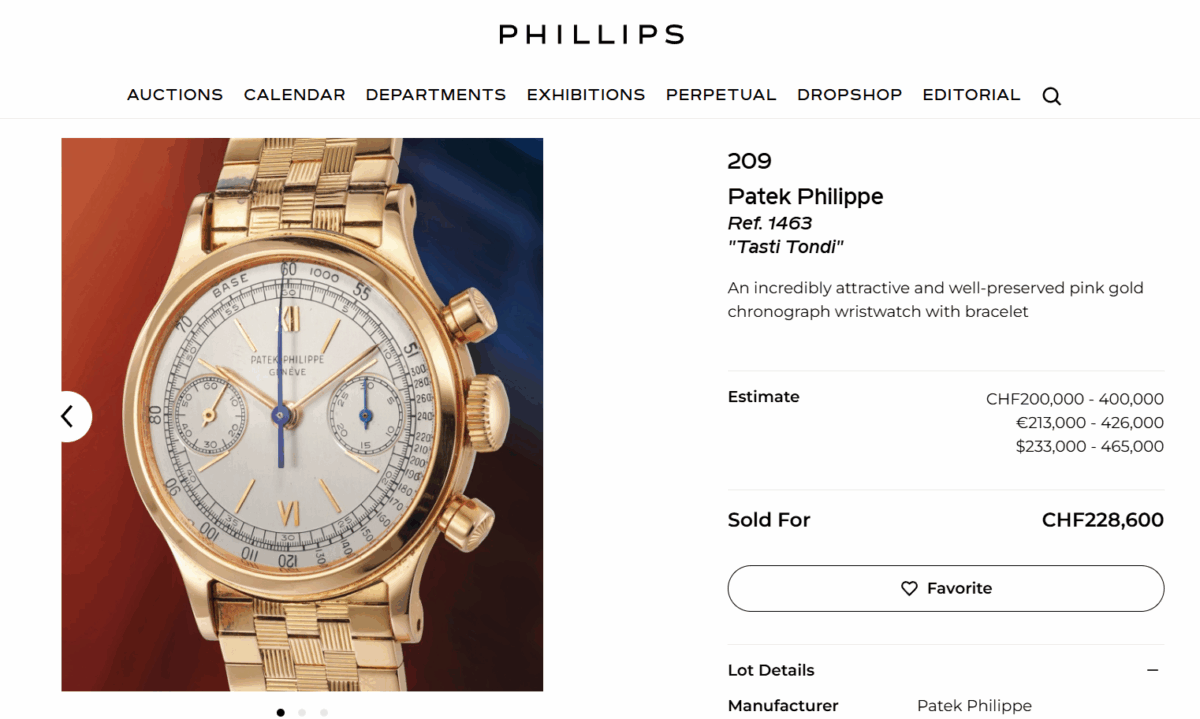

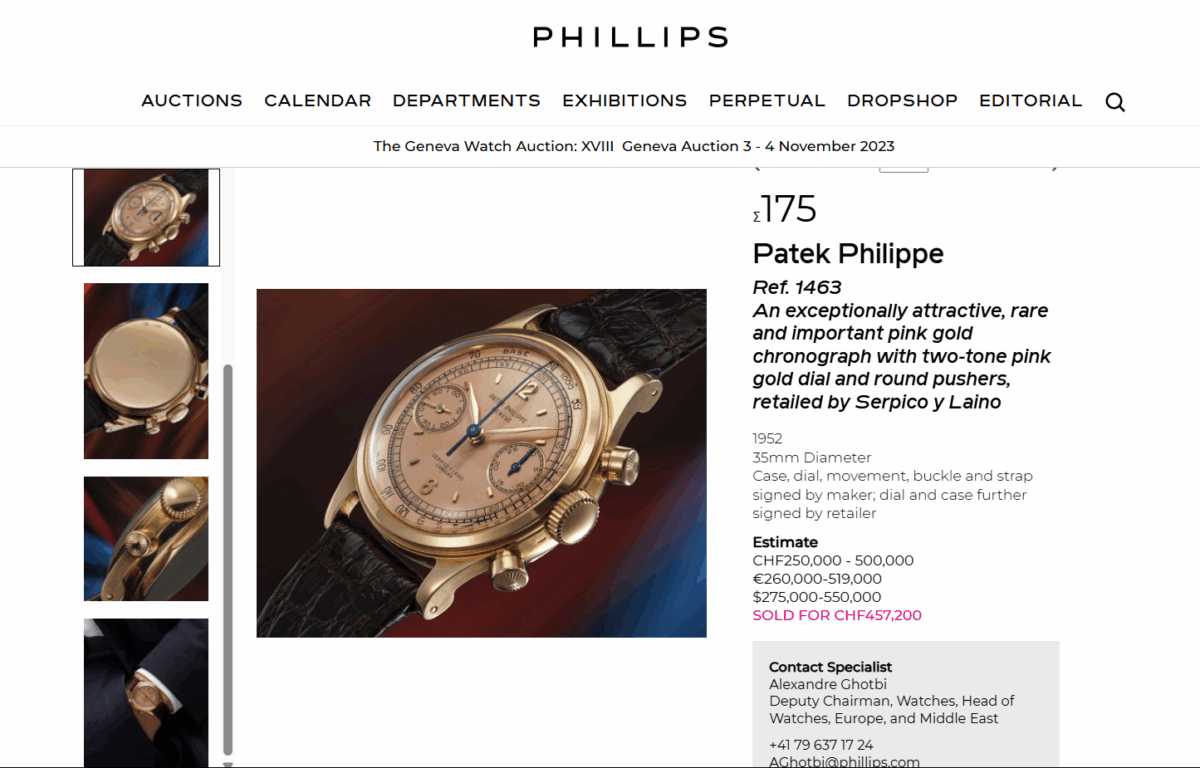

This article is mainly about the Patek Philippe Ref. 1463. The “Tasti Tondi” – That’s how the Italians call it; it means “Round Pushers”, just like how we Moroccans call a vintage Porsche 911 “The little eyes” – for its round headlights, of course.

However, this wouldn’t be a “Deep Dive” without a mention of the iconic reference’s predecessors and successors. Upgrades and changes. Peers and some family members.

But first, a special shout-out to my dear friend Mr. Arnau, the vintage Patek connoisseur, for providing the incredible wrist shots you’ll see below.

Here’s a quick summary to help you navigate through this heavy piece:

- What The Hell is a “Chronograph”?

- Why Patek’s?

- Is The 1463 Cool Just For Its Italian Nickname?

- Is There More?

- Where Are We Now?

What The Hell Is a “Chronograph”?

And to that I say, fair enough. What IS a chronograph?

Well, put simply, in the world of horology, a chronograph is the wristwatch equivalent of a stopwatch wearing a tuxedo. It’s the complication that lets you measure elapsed time—perfect for recording your lap around Le Mans, or, more realistically, how long it takes your pasta to be al dente (Mamma Mia !)

The chronograph’s roots go way back to 1821, when Nicolas Rieussec created the first version to time horse races. But the chronograph truly found its groove once automobiles began doing in minutes what horses needed hours to accomplish.

A chronograph lets you measure time intervals thanks to extra pushers (usually at 2 and 4 o’clock) and sub-dials. Push one button to start, push it again to stop, and another to reset.

Some chronographs go full throttle with things like: Flyback (restart without resetting), Rattrapante (split-seconds—timing two events at once), Or the very modern high-frequency types which can measure to 1/1000th of a second (Outrageous).

Sure, your phone can time things. But a chronograph does it with gears, levers… All analog and cool as heck.

Right, but you might be asking yourself…

Why Patek and Patek’s Chronographs?

And to that I say: Be fucking for real, it’s Patek Philippe.

It’s arguably the most prestigious thing on planet Earth. Yes. More elite and High-caliber (pun intended) than Schiaparelli dresses, Porsche and Ferraris, a stay at the Marriott… you name it.

Mind you, I’m not only referring to the financial aspect of it. It’s the meticulousness, the resistance to the test of time, the historical presence, the innovative spirit… I say this to make sure none of you guys make the mistake of assuming that money is what life is all about. Just make sure to have some kind of taste and sense of direction before you become rich. The wealthy tend to get their vision blurred when bombarded with ego traps and unhealthy shopping addictions. Just look at the ones with their fat Richard Milles… God have mercy on their souls.

Let me digress, Patek’s chronographs.

Before Patek started making in-house chronograph movements in the 2000s, their vintage chronographs used ébauches (base movements) from manufacturers like Valjoux and Lemania—but heavily modified, finished, and regulated by hand to Patek’s elite standards.

The level of hand-finishing—anglage, black polishing, Geneva stripes—was so high that modern brands still use them as benchmarks.

Let me tell you guys about a few very important references then we’ll dig into the holy grail — The Tasti Tondi. Stay with me now.

The ref. 130

What started it all was the maison’s Ref. 130, introduced in the 1930s, which is one of their earliest serially produced chronographs. Clean dial layouts, restrained proportions, and exceptional movement quality.

Before the 130s, Patek made chronographs sporadically, often as one-off commissions. Like in 1922 when they made the world’s first Split-Second chronograph wristwatch, later sold at Sotheby’s NYC in 2014. More on that in a bit.

The Ref. 130 marked a turning point — it was their first attempt at creating a consistent line of chronographs. But “serial” in Patek terms still meant ultra-low quantities, often under 100 per configuration over decades. Chronographs before this were typically utilitarian, made by brands like Longines or Universal Genève for military or scientific purposes. Patek brought refinement with gold or platinum cases instead of base metals, elegant Breguet or baton hands, enamel-signed dials, balanced subdial spacing… and more and more and more.

This article is, as mentioned previously, mainly about the Ref. 1463. However, I can’t fast forward 20 years of innovation without noticing and analysing the bridge that facilitated the crossing. The production chain of the Ref. 130 kept alive from the mid-30s to the 60s. From 1936 until 1964. This was the “gentleman’s chronograph”. Thin bezel, flat pushers, Snapback case, not waterproof. With a modified Valjoux 23. Straight to the point.

“The reference 130 was made in approximately 1,500 examples between 1936 to 1964, and was an absolute marvel of design architecture. Indeed, close your eyes and imagine the most pure and beautiful expression of a gentleman’s chronograph, and you will have come pretty close to the reference 130.”

Alexandre Ghotbi – Revolutionwatch.com

The ref. 530

Later, 1937-62, came the Ref. 530.

Put simply, it’s the 130, but bigger. As in 36.5mm. Crazy, right? 36mm was “Big” back then.

The design? Straight out of the sector dial dream factory, at least in the first wave. These early 530s were mostly produced in the late ’30s and came strapped with 19mm lugs. But then came the Croisier cases (named after the case maker, Georges Croisier), with chunkier 21.5mm lugs, which made the whole thing look even more commanding on the wrist.

Despite the size increase, the watch retained the elegance and refinement expected from Patek Philippe. It used the same hand-wound chronograph movement architecture, based on the Valjoux 23 ébauche, as the ref. 130, but with Patek’s hallmark refinishing, decoration, and regulation. These movements were transformed in-house with meticulous attention to detail, bringing them to haute horlogerie standards. In short, while the engine under the dial may have started as a Valjoux, once it left the Patek workshops, it was a very different machine—Geneva-striped, bevelled, and fit for one of the most respected names in watchmaking.

The ref. 530 was produced in extremely limited numbers. Today, only 28 examples in yellow gold are known, 14 in pink gold, and fewer than 10 in stainless steel. The steel variants are particularly fascinating: not only are they exceedingly rare, but their cases were manufactured in two distinct lug widths. Early steel versions from the late 1930s were fitted with 19mm lug spacing and typically featured sector dials, while a later batch, likely produced with cases from Georges Croisier, had wider 21.5mm lugs. This subtle but meaningful difference gives the later watches an even stronger visual impact, emphasizing the bold proportions and modern feel of the reference decades before larger watches became the norm.

One of the most collectible variants of the ref. 530 is the example with applied Breguet numerals. These are not just rare—they’re unique. To date, only one known ref. 530 has surfaced with this specific dial configuration. Given the already minuscule production numbers of the model overall, dial variations like these elevate specific examples into the realm of true grail watches.

The coolest part of it all is the fact that the influence of the 530 didn’t stop with its mid-20th-century production run. When Patek Philippe introduced the reference 5170 in 2010, it was widely seen as a modern heir to the 530’s legacy. Although the 5170 was powered by Patek’s in-house caliber CH 29-535 PS rather than a reworked Valjoux or Lemania base, the aesthetic and proportional similarities were evident. Long, elegant lugs, a pure dial layout, and a restrained case design all echoed the quiet power of the 530. It was a subtle homage to a watch that had, in many ways, defined what a high-end chronograph could be long before that became an industry standard.

The ref. 533

I mean no disrespect when I say that there isn’t much to say about the ref. 533. That’s because it’s the closest model to the 130. The only difference is the flat bezel on the 533, the Calatrava-style case, and square pushers with very long skinny lugs.

The 533 was in production from 1937 to 1957, with a total estimated at about 350 pieces, with a majority in yellow gold and a small number cased in pink gold. It is definitely a more “under the radar” reference that offers collectors a rare watch fully integrating “Patek Phillipe Chronograph” design identity, but “cheaper”.

The ref. 591

This one was unique. Something very different from the previous references. New elements. New case design and designer, etc.

So, Patek Philippe introduced reference 591 in 1938, and it marked a sharp stylistic turn from the brand’s more conservative chronograph designs of the era. While its technical foundation remained solidly within Patek’s tradition of hand-finished, hand-wound chronograph movements, the visual language of the 591 stood apart. Instead of following the rounded, minimalist contours of references like the 130 or 533, the 591 introduced bold new case architecture: sharp, angular lines, a concave bezel, and distinctive, stylized lugs that would earn the model its nickname—Fagiolino, or “little bean,” a name affectionately given by Italian collectors for the lug shape’s resemblance to a small curved legume. The Italians and their nicknames…

The case was made by Wenger, one of the notable case manufacturers used by Patek in that era. At 34mm in diameter, it was notably larger than most other chronograph references produced in the 1930s, many of which hovered around the 31–33mm range. That increase in size, paired with the geometric silhouette, gives the 591 a surprisingly modern presence on the wrist today.

Production numbers for the 591 were extraordinarily low, even by Patek Philippe’s already limited standards. To date, just 19 examples in yellow gold are known to exist, and 27 in pink gold. No steel versions are known, making this reference one of the scarcest vintage chronograph models Patek ever produced. It’s a watch that surfaces only occasionally in the auction circuit, and while it doesn’t always achieve the sky-high prices of references like the 530 or 1518, it has its people.

The ref. 1579

Still getting creative here.

Introduced in 1943, Patek Philippe’s reference 1579 stands out in the brand’s chronograph lineage for its distinctive case design. The watch features faceted lugs, often referred to as “spider lugs,” which set it apart from other models of the era. These lugs, crafted by the renowned case maker Wenger, contribute to the watch’s unique aesthetic and have become a defining characteristic of the reference.

The dial, produced by Stern Frères, came in two distinct series: the first, from 1943 to 1949, featured Arabic numerals with baton indexes and baton or feuille hands; the second, from 1950 to 1964, showcased Arabic numerals with square indexes and feuille hands.

Approximately 470 examples of the reference 1579 were produced between 1943 and 1964. Of these, around 250 were in yellow gold, 185 in pink gold, and a few in stainless steel and platinum. Notably, only three examples are known to exist in platinum, making them exceptionally rare.

And Now, Finally, The ref. 1463 “Tasti Tondi”.

“It is safe to say that Patek Philippe’s reference 1463 chronograph is considered by collectors as one of the most attractive and utterly bombastic vintage chronographs of our times.”

Alexandre Ghotbi.

Is The 1463 Cool Just For Its Italian Nickname?

This is my holy grail. My Roman Empire. The only unattainable thing I’m happy not attaining.

Let me dig in.

Patek Philippe’s reference 1463 isn’t just a collector’s favorite—it’s the kind of chronograph that rewrote the rules for what a high-end, technically proficient wristwatch could look and feel like in the mid-20th century. Introduced in 1940, it broke new ground as the brand’s first chronograph to feature a water-resistant case. This was made possible thanks to a screw-down caseback and round pump-style pushers—an engineering solution that, at the time, was a rarity in elegant Swiss watchmaking. These rounded pushers earned the model its now-famous Italian nickname, Tasti Tondi, or “round buttons.” But these weren’t delicate little things—they were pronounced, easy to operate, and exuded a robust charm, suggesting the watch was made to be used, not just admired.

The case itself was produced by Taubert Frères, a respected Geneva-based casemaker with deep expertise in crafting hermetically sealed cases. Taubert was known for manufacturing the famous decagonal screw-down casebacks, which offered far better protection against moisture and dust than the snap-on cases typically used by Patek Philippe at the time. This allowed the 1463 to thrive as a sort of sportier cousin to the more delicate reference 130.

Measuring 35mm in diameter, the 1463 was generously sized for its era, with a thick, stepped bezel and sharply faceted lugs that gave the watch presence and proportion. That made it both refined and rugged—a watch equally at home under the cuff of a tailored suit or strapped on the wrist for a spirited drive in a pre-war Alfa Romeo. The fact that it was water-resistant made it feel like a modern machine, and in many ways, it was. It was made to live with you.

But hey, let me make something clear now.

In the 1940s, calling a watch “water-resistant” didn’t mean you were strapping on dive gear and descending into the abyss. It simply meant your watch wouldn’t give up the ghost the moment it met a splash. You could wade into the sea, rinse off under a beachside shower, or catch a wave of champagne spray at a Riviera party without worry. That was the luxury: in freedom.

Think of someone like Gianni Agnelli, who famously liked to make his entrance at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc by leaping from a hovering helicopter into the Mediterranean. As our friends from Revolution Watch magazine put it, if you were one of his guests, would you really want to be the guy on the sidelines explaining, “Sorry, I can’t. My watch can’t get wet.”? The reference 1463 spared its wearer from such indignities.

Put simply, it wasn’t built for deep-sea exploration; it was built for flexibility.

Now, back to what makes the 1463 arguably the most beautiful chronograph in history.

Dial variations were numerous, with layouts ranging from simple baton markers to exotic configurations with Breguet numerals, two-tone finishes, or pulsation scales. These dials were produced by Stern Frères, the legendary dial maker that supplied Patek with most of its faces throughout the 20th century. One of the rarest configurations? A pink gold case with a pink dial—watches so rarely seen that when they do appear at auction, they get serious attention and even more serious numbers.

Speaking of numbers, around 740 examples of the reference 1463 were produced between 1940 and 1965. Of those, approximately 405 were in yellow gold, 145 in pink gold, and roughly 190 in stainless steel, though some sources place the steel count slightly lower. Pink gold versions are especially rare, with about 55 known examples documented publicly today. The stainless steel models, however, are often the most coveted, particularly for collectors who appreciate the utilitarian charm and rarity of a complicated steel Patek from the golden era.

This reference wasn’t just a novelty—it signaled a quiet shift in how complicated watches could be used. Before the ref. 1463, the idea of jumping into a pool with your Patek Philippe would have been ludicrous. After the ref. 1463, the rules changed. You can have both elegance and functionality, too. It’s no wonder that the watch found favor with cultural icons like Mr. Duke Ellington, who owned a split-seconds variant, ref. 1563 (more on it in a bit), which is a testament to how the reference balanced artistry and utility, just like his music.

In today’s vintage market, the 1463 remains one of the most admired and actively pursued references from Patek Philippe’s back catalog. Its mix of durability, design, and exclusivity makes it feel incredibly present, despite being over 80 years old. And for all its elegance, it still carries a sense of practical purpose.

Is There More?

The Split Second Chronographs.

Again, what the hell is a split-second chronograph ?!

In a nutshell: Split-seconds chronograph (also known as a rattrapante) = a chronograph that can time two intervals that start together but end at different times. It operates with two overlapping central seconds hands and features a split pusher to stop and release one of the hands independently.

When you start the chronograph, the two central chronograph seconds hands begin to move together, perfectly overlapping. One of them is the regular chronograph hand; the other is the split-seconds (rattrapante) hand. These hands remain together as long as the function runs. Once you push a secondary pusher usually located in the crown or on the case you can stop the split-seconds hand while the main chronograph hand keeps running.

It’s cool, but very, very hard to make.

I say that because although Patek Philippe’s perpetual calendar chronographs like the legendary references 1518 and 2499 cemented the brand’s place among the titans of watchmaking, it was the split-seconds reference 1436 that quietly held the title of the most mechanically complex wristwatch in the company’s lineup for decades.

So, let’s get into it.

Patek Philippe’s vintage split-seconds chronographs references 1436, 1563, and 2512 represent some of the most technically sophisticated and aesthetically refined timepieces in the brand’s storied history.

The Reference 1436

The First Serially Produced Split-Seconds Chronograph.

Introduced in 1938, the reference 1436 holds the distinction of being Patek Philippe’s first serially produced split-seconds chronograph wristwatch. Over its production life until 1971, approximately 140 examples were crafted, predominantly in yellow gold, with a few in pink gold and an extremely limited number in stainless steel.

The 1436 housed the caliber 13-130 movement, based on a Valjoux ébauche, and featured a split-seconds (rattrapante) mechanism. Early models utilized the crown to operate the split-seconds function, while later versions incorporated a coaxial pusher within the crown for improved functionality.

Dial variations included configurations with Breguet numerals, oversized registers, and unique inscriptions. The cases were crafted by renowned case makers like Emile Vichet and Ponti Gennari, contributing to the watch’s refined aesthetics.

Notably, a stainless steel 1436 achieved a staggering hammer price of CHF 3.3 million at a Phillips auction in 2016, underscoring the model’s desirability among collectors.

The Reference 1563

The more advanced “Tasti Tondi” sister. Remember how the 1463 was the normal chronograph and the one known as “Tasti Tondi” ? Well the 1563 is the same watch with a split seconds chrono complication. That’s it.

Only three known examples exist, one of which belonged to jazz legend Duke Ellington and now resides in the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva.

Sharing the water-resistant screw-back case and round pushers of the 1463, the 1563 incorporated the same foundational 13 lignes caliber, enhanced with the rattrapante mechanism, of course.

One particularly interesting example features luminous Breguet numerals and hands, a unique configuration confirmed by Patek Philippe’s archives. This watch was sold at Christie’s Geneva in 2013 for CHF 1.45 million, highlighting its exceptional value.

Let me just say it again for it to sink in: There are only 3 (that we know of).

Where Are We Today?

Well, Patek is the house of innovation and excellence. No one could ever discredit or deny their place as the most “Hauts” of the Haute Horlogerie maisons.

Patek Pillipe went on to develop more complicated chronographs.

Chronographs that weren’t just chronographs, but something something chronographs. More split-second chronographs and Perpetual calendar chronographs. Very Grand indeed.

could write a whole piece, even longer than this one, about modern takes on the split-second chronos and most importantly perpetual calendar chronographs of this époque.

But to name a few, so that you guys know what I’m referring to:

- The ref. 1518 – I freaked out when it was mentioned in Netflix’s The Gentlemen – which was the first wristwatch in history to combine a chronograph and a perpetual calendar in a serially produced format. This was a bold move during World War II—while most brands were focused on tool watches and survival, Patek Philippe was introducing high-complication dress pieces aimed at the most elite clientele.

- The ref. 2499. A holy grail for many. It replaced the 1518 in the early ’50s and is arguably the most famous perpetual calendar chronograph ever made. It went in production for over three decades in four series, only about 349 examples were made, still incredibly rare by modern standards.

… etc

Closing Statement:

This took a lot of courage. Between self-doubt about my worthiness to write extensively about such a significant subject, and the many rabbit holes I fell into between researching one reference or another… Many nights were spent thinking about whether or not I should indulge in this challenging adventure.

The soundtrack behind this article was powered mostly by Booker T., Albert King, and Jimmy McGriff—legends among legends. I mention this not just to set the mood, but to help explain the emotional swings you might notice throughout, and perhaps to excuse how hard I gush over the “Tasti Tondi.”

What I would like to close with, is by giving flowers to those who guided me throughout this piece. I am by no means a Patek savant, but I read and studied a lot.

Thank you to Mr. Wei Koh and Mr. Alexandre Ghotbi from Revolution Watch, for their 10,000 words article titled: The Complete Guide to Patek Philippe Vintage Chronographs. Oh yes, you read it correctly. It’s a 10,000 words article. And one that I read at least 7-9 times. It was just so fun! The exchange between Mr. Wei’s picks and Mr. Alexander’s thoughts made the piece as dynamic as Patek’s innovations.

Thank you to Mr. Marcus Siems from Goldammer for his amazing Reference Guide to Patek Philippe Chronographs (1936-71). This piece really laid everything out for me and served as a clear guide through the many references, variations, and their specs.

The Patek Philippe “Tasti Tondi” article from Italian Watch Spotter, written by Mr. Fabrizio Bonvicino, takes all the credit for making the ref. 1463 My grail watch. I had my full circle moment when I remembered reading it in 2021 and being like “oh wow”.

An honorable mention would be THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO THE CHRONOGRAPH by Mr. Samuel Colchamiro from Analog Shift. An article that made me take a step back and look at the bigger picture of what a chronograph truly means and how much of a quintessential complication it has been throughout history and historical moments. The iconic moments, the iconic people, and their iconic wrist companions.

Hodinkee was, of course, a source of great value. A source you can trust when it comes to being on point with every significant/rare Patek Philippe chronograph sighting in auctions and auction houses.

On a personal note, thank you to Mr. Arnau Martínez Belda, a very dear friend of mine who happens to be a true vintage Patek Philippe connoisseur and an auction freak. Most of the hand-held photographs you’ve seen in this article are his. So, gracias amigo!

And thank you guys for reading! I hope I didn’t disappoint.

I find it only suitable for me, as the guy who built this, to be discussing and writing about such heavy subjects. The news and the trendy stuff are, of course, cool, but this is real horology, and I’m a real horology lover.

Until next time, take care.

Walid.

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND NEVER MISS A THING !

Patek Philippe chronographs are revered for their exceptional craftsmanship, technical prowess, and elegance. As some of the most sought-after watches in the world, Patek Philippe has a long history of producing chronographs, from simple hand-wound versions to highly complicated timepieces with additional functions.